Queue automaton

A queue machine or queue automaton is a finite state machine with the ability to store and retrieve data from an infinite-memory queue. It is a model of computation equivalent to a Turing machine, and therefore it can process any formal language.

Contents |

Theory

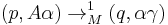

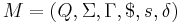

We define a queue machine by the six-tuple

where

where

is a finite set of states;

is a finite set of states; is the finite set of the input alphabet;

is the finite set of the input alphabet; is the finite queue alphabet;

is the finite queue alphabet; is the initial queue symbol;

is the initial queue symbol; is the start state;

is the start state; is the transition function.

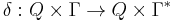

is the transition function.

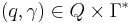

We define the current status of the machine by a configuration, an ordered pair of its state and queue contents  (note

(note  defines the Kleene closure or set of all supersets of

defines the Kleene closure or set of all supersets of  ). Therefore the starting configuration on an input string

). Therefore the starting configuration on an input string  is defined as

is defined as  , and we can define our transition as the function that, given an initial state and queue, takes the function to a new state and queue. Note the "first-in-first-out" property of the queue in the relation

, and we can define our transition as the function that, given an initial state and queue, takes the function to a new state and queue. Note the "first-in-first-out" property of the queue in the relation

where  defines the next configuration relation, or simply the transition function from one configuration to the next.

defines the next configuration relation, or simply the transition function from one configuration to the next.

The machine accepts a string  if after a (possibly infinite) number of transitions the starting configuration evolves to exhaust the string (reaching a null string

if after a (possibly infinite) number of transitions the starting configuration evolves to exhaust the string (reaching a null string  ), or

), or  [1]

[1]

Turing completeness

We can prove that a queue machine is equivalent to a Turing machine by showing that a queue machine can simulate a Turing machine and vice-versa.

A Turing machine can be simulated by a queue machine that keeps a copy of the Turing machine's contents in its queue at all times, with two special markers: one for the TM's head position, and one for the end of the tape; its transitions simulate those of the TM by running through the whole queue, popping off each of its symbols and re-enqueing either the popped symbol, or, near the head position, the equivalent of the TM transition's effect.

A queue machine can be simulated by a Turing machine, but more easily by a multi-tape Turing machine, which is known to be equivalent to a normal single-tape machine. The simulating queue machine reads input on one tape and stores the queue on the second, with pushes and pops defined by simple transitions to the beginning and end symbols of the tape.[2] A formal proof of this is often an exercise in theoretical computer science courses.

Applications

Queue machines offer a simple model on which to base computer architectures,[3][4] programming languages, or algorithms.[5][6]

See also

- Computability

- Turing machine equivalents

- Deterministic finite automaton

- Pushdown automaton

- Tag system

- Manufactoria, a browser flash game tasking the player with implementation of various algorithms using a queue machine model.

References

- ^ Kozen, Dexter C. (1997) [1951]. David Gries, Fred B. Schneider. ed (hardcover). Automata and Computability. Undergraduate Texts in Computer Science (1 ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 368–370. ISBN 0-387-94907-0.

- ^ Rus, Teodor. "Variants of Turing Machines". Lecture Notes Covering Theory of Computation. University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, 52242-1419. http://www.cs.uiowa.edu/~rus/Courses/Theory/Notes/turing3.pdf. Retrieved 2007-11-06.

- ^ Feller, M.; M.D. Ercegovac (1981). "Queue machines: An organization for parallel computation". Lecture Notes in Computer Science 111: 37. doi:10.1007/BFb0105108. http://www.springerlink.com/content/m8w6x22741k5u093/. Retrieved 2007-11-06.

- ^ Schmit, Herman; Benjamin Levine, Benjamin Ylvisaker (2002). "Queue Machines: Hardware Compilation in Hardware". 10th Annual IEEE Symposium on Field-Programmable Custom Computing Machines (FCCM'02): 152. doi:10.1109/FPGA.2002.1106670. http://doi.ieeecomputersociety.org/10.1109/FPGA.2002.1106670. Retrieved 2007-11-06.

- ^ Moore, Christopher (1999-09-20). "Queues, Stacks, and Transcendentality at the Transition to Chaos". Algorithms Project's Seminar. INRIA. http://algo.inria.fr/seminars/sem99-00/moore1.html. Retrieved 2007-11-06.

- ^ von Thum, Manfred (2007). "A queue machine for evaluating expressions". LaTrobe University. http://www.latrobe.edu.au/philosophy/phimvt/misc/queue.html. Retrieved 2007-11-06.